Artist Alex Julyan reflects on her residency in the New Forest

PUBLISHED ON: 19 JANUARY 2024My work isn’t made with signature materials, or by a particular method. Instead, each project is directed by an intention to draw on diverse ideas, histories and experiences, and to pull these threads towards a central point. Playfulness, absurdity and chance hold a significant place in the process, as do the skills and knowledge of the people I encounter. Art isn’t an exact science, its edges are permeable and shifting, and it’s always contingent on the circumstances in which it’s made.

In Preparation

It’s customary to make lists when moving from one place to another. List-making serves a practical purpose as well as a ritualistic one. In addition to items of practicality and comfort, the packing list is an inventory of imagining and hope.

I leave the city in which I am one of nine million inhabitants and in just over two hours the imagined forest becomes a reality. There’s no seismic shift or atmospheric adjustment on touchdown, perhaps because the list was thoroughly made and this time long anticipated.

I’ve arrived without a plan – or more precisely – with a deliberate ‘non-agenda’. My intention is to attune myself to Forest life, let the days unfold and see what emerges from a month of immersion. Resident artists are invited in their capacity as outsiders to look in on the forest: its history, ecologies, people and governance, and to find creative paths through it. My time here is part of a creative continuum, one in which the before and after are as important as the time spent here. If my no-plan goes to plan I’ll navigate blind alleys, stumble and trip, and re-arrange some creative habits and thoughts. Creative work can be a solitary pursuit, though sometimes it’s a collaboration between experts and strangers. This looks to me like a Rubik’s cube of people, places and conversations.

Peregrinations

As a committed non-driver getting around is my first creative challenge, but legs are wonderful things and I have a pair, so walking and cycling is the name of the game. I think of Wordsworth and his alleged 175,000 miles of walking. As he so eloquently demonstrated, getting about by leg and foot sets a particular pace and perspective, a way of engaging at close quarters with texture, colour, sound, atmosphere, weather, ecologies, histories, people and scales.

Getting lost is an essential skill. The American pioneer and folk hero Daniel Boone famously once said, ‘I can’t say I was ever lost, but I was once bewildered for about three days.’ In these times of Google Maps and Google Earth, we are encouraged to imagine that being lost is a form of stupidity or close to a catastrophe. I’m a stranger in the Forest and a paper map and compass are serving me well. I’m lost just enough and not too much. I meet people who are as lost as I am and an array of helpful folk who give directions that span a wide spectrum of accuracies.

Once lost, I toggle between imagining I’m a boy scout who deftly reads the signs (moss on the north side of the tree, low sun in the west, ant nests in the south) and allowing myself to disengage from the need to know where I’m going. This approach is only possible when you know that a road/train station/cappuccino is only a few miles away and the Rocky Mountains much further. Nevertheless, it’s a liberation which forces me to concentrate on where I am and not where I’m going. Stopping to look around, to stare at the sky, the ground and the map, and connecting it all together before deciding that I’m still lost is surely a wonderful state of being.

Majesty

In this year of the Coronation the term ‘Majesty’ will elicit a wide range of opinions, but who could disagree that the Scots Pines towering skywards up to 30 metres and with such a regal posture are the essence of majesty. These hardy, straight-standing trees may not have the reputation of the ancient oaks or beech, but for me, there is a compelling sense of drama and beauty about them. On days when the sun and rain alternate and the trees glisten with raindrops, the pines take on a theatrical presence. Their sweeping branches filter shafts of ethereal sunlight onto the needled forest floor and the overall effect mimics a painted backdrop in front of which wolves might lope, or fairies cavort.

I’ve tried so many times to comprehend their scale, I want to hold the image of them, or rather the image of me in relation to them in my mind’s eye and take it back to the city. They are the closest thing I can find to a tall building in the Forest.

Outside in

The layers and layers and lifetimes of knowledge that reside here constantly underline the parallels as well as the differences between the city and the Forest. There’s so much complexity that my outsider status becomes more, not less, apparent with each passing day. The more I discover the less I know.

Visiting the New Forest Archive in Lyndhurst is another way to experience the slippery nature of this place and how it’s shaped by people as much as nature. An accommodating archivist pulls the lid from a box where a ventriloquist’s dummy cheekily reclines on a bed of wadding, his mouth is agape, but he has little to say for himself as to why he is here.

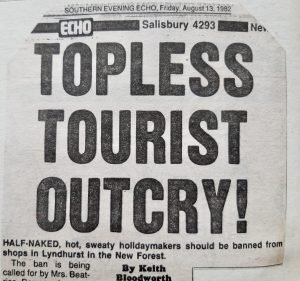

I leaf through a collection of scrapbooks dated 1966-88. Their pulpy, coloured pages disclose a wealth of newspaper cuttings, carefully collated and pasted-in by Councillor Deardon – an upstanding, but seemingly agitated man (judging by his choice of snippets). Headlines such as ‘Forest a vast Butlins’, ‘Confidence breach rouses anger’, ‘Thin end of the wedge’ and ‘We will be a laughing stock’ hint at the local (and journalistic) concerns that the Forest was going to hell in a handcart. These articles plot dissent and disgust on a range of Forest issues, some of which continue to occupy the pages of the local papers. But what these articles really chart is the eternal conflict between man and nature, conservation and change.

Grand Designs

Article 25 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognises the right to adequate housing, but we all know that for many this does not manifest as a reality. In these tumultuous times, I’ve been thinking about the nature of shelter, of fixed abodes and territorial claims.

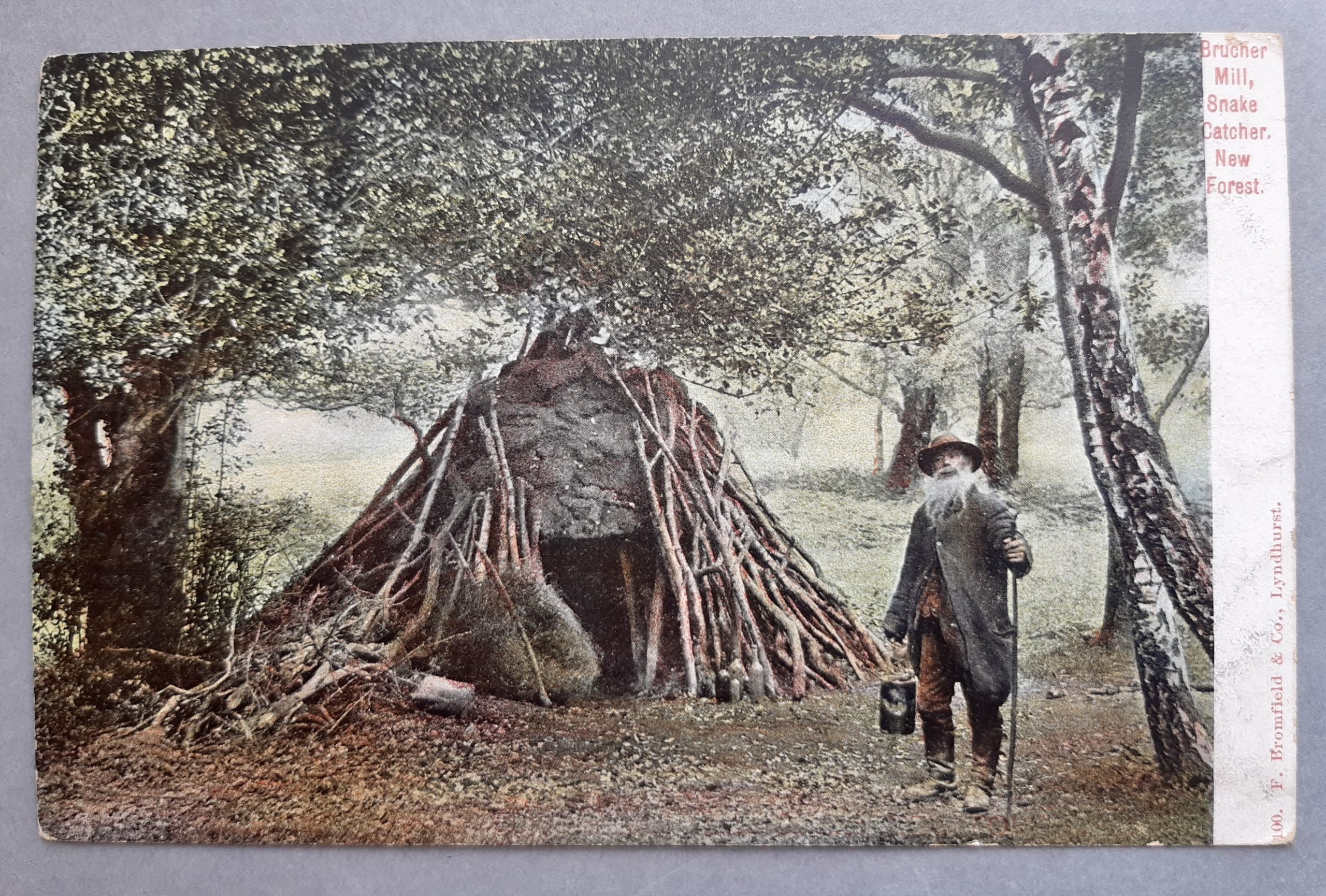

Once, Gypsy Benders formed part of the Forest landscape. These temporary shelters made from hazel branches and cloth were the ultimate modular home: a vernacular kind of architecture that could be erected, dismantled and re-erected according to circumstance. Now the Forest is peppered with uninhabited makeshift dens constructed not from a primal need for shelter, but a desire to play and create. As I walk or cycle I catch these structures in my peripheral vision, I’m surprised by their number and intrigued by the range of typologies and construction methods. Some are barely finished, assembled in haste using the ‘leaning’ method. Others, constructed over months or even years demonstrate an ambitious balancing and weaving of logs, branches and sticks. They remind me of the Cardinals’ hats that hang in different states of decay in Toledo’s great cathedral, each one symbolising a person and set of intentions which nature ultimately reclaims.

My accommodation boasts a fair-sized TV. On my second night of channel surfing, I alight on ‘Grand Designs’ with its jaunty architect-presenter: Kevin McLoud. He extolls the virtues of vision, teamwork and sustainability. Isn’t this the very essence of den building?

Good effort

A pile of borrowed wood sits on the pavement outside the New Forest Heritage Centre. With the permission of their director, I’ve decided to invite some spontaneous construction around two metal bollards. The results have the intentionality of a den, without ever becoming one. Veteran den builders, enthusiasts, reluctant-retired Boy Scouts, a nuclear power coordinator, a physiotherapist, dog club members, dolls house collectors and a chemistry professor construct and dismantle a variety of thickety structures over four days. A passing employee for Ordinance Survey observes that this disruptive building approach is much needed in the corporate world she inhabits. Children are the dominant and intuitive builders, often instructing, negotiating and narrating as they progress. Each contributor works to a vision or memory that resides in their mind’s eye and those are ultimately the dens that they make.

Beasts

My father-in-law apparently once owned a pig called Homer and taught him tricks. I’m not sure that the New Forest porkers are so compliant, this is Pannage season and they have an abundance of acorns on their minds. Sadly, my only encounter with these contented swine is a glimpse from the top deck of the number six bus as it hurtles along Lyndhurst Road.

If you come from the city, it’s impossible not to be seduced by the pigs, ponies and donkeys, especially when you find them loping along village streets and setting the rush-hour pace. Someone tells me a pony entered the Tesco in Brockenhurst as its automatic doors opened to signal bargains within. Of course, anywhere where animals have adapted to human environments and habits is a cause for concern, and as the clocks go back the discord between our world and theirs is amplified, the next few months will be a perilous time for the ponies.

Into the woods

As a novice den-builder and city-dweller, I’ve neither the experience nor technique that many of you honed in your woodland youths. Luckily, I’m an artist whose stock-in-trade is the manipulation of found and familiar materials and in that respect, I’m in my element.

A well-chosen site, a plentiful stock of wood, focus and application are the essential elements of den building. I discover that a happy accident is as valuable as a considered move. The material play of the wood for example – the pliability of holly and hazel, the snapping beech and rotted pine all come into play, as does the discrepancy between vision and reality. I’m drawn to the idea of the den as construction within my reach. It’s the most basic form of architecture, an emergency shelter or playful hideout. The hours I spend obsessively gathering and making in the sun, wind and rain result in a woven structure in a forest glade. It’s nowhere near reaching my ambitions for it, but by the den rule book, it’s a good first attempt that I gift to passers-by and nature to progress its course.

Alex Julyan is the fourth New Forest National Park Artist in Residence, she underwent her residency in October 2023 and will exhibit in May 2024 at SpudWORKS.